Uber has acquired bike-sharing startup JUMP for an undisclosed amount of money. This comes shortly after TechCrunch reported that JUMP was in talks with Uber as well as with investors regarding a potential fundraising round involving Sequoia Capital’s Mike Moritz. At the time, JUMP was contemplating a sale that exceeded $100 million. We’re now hearing that the final price was closer to $200 million, according to one source close to the situation.

JUMP’s decision to sell to Uber came down to the ability to realize the bike-share company’s vision at a large scale, and quickly, JUMP CEO Ryan Rzepecki told TechCrunch over the phone. He also said Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi’s leadership impacted his decision.

“I had a chance to spend a couple of evenings with him, and really talk through his vision for the business and our vision, and saw a lot of alignment,” Rzepecki said.

He noted that while Uber had a rocky 2017, he’s optimistic Uber is on the right track.

“I think it’s really on the right course now and [Khosrowshahi] believes the way we approach working with cities and our vision for partnering with cities” aligns with Uber’s mission, Rzepecki said. “That was important for me and his desire to do things the right way. This is a great outcome and gives me a chance to bring my entire vision to the entire world.”

Meanwhile, becoming a top urban mobility platform is part of Uber’s ultimate vision, Khosrowshahi told TechCrunch over the phone. As more people live in cities, there will need to be a broader array of mobility options that work for both customers and cities, he said.

“We see the Uber app as moving from just being about car sharing and car hailing to really helping the consumer get from A to B int he most affordable, most dependable, most convenient way,” Khosrowshahi said. “And we think e-bikes are just a spectacularly great product.”

As part of the acquisition, JUMP employees will join Uber’s team but the bike-share company will carry on as an independent, wholly controlled subsidiary, Rzepecki said.

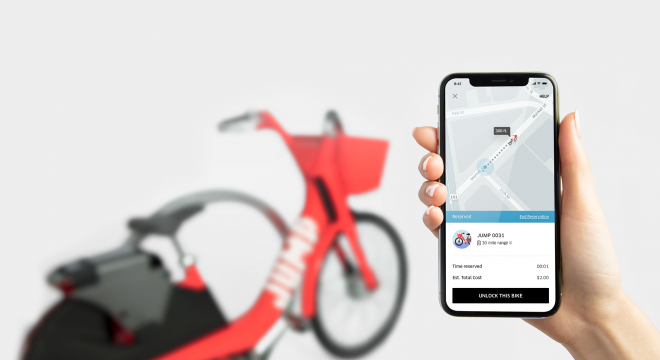

JUMP is best known for operating dockless, pedal-assist bikes. JUMP’s bikes can be legally locked to bike parking racks or the “furniture zone” of sidewalks, which is where you see things like light poles, benches and utility poles. The bikes also come with integrated locks to secure the bikes.

Uber’s acquisition of JUMP is not too surprising. In January, Uber partnered with JUMP to launch Uber Bike, which lets Uber riders book JUMP bikes via the Uber app. The majority of trips, however, still come through the JUMP app, Rzepecki said. For the time being, JUMP’s app will continue to exist but that may eventually change.

“It’s our hope the experience will be more deeply integrated into the Uber app moving forward and reflects what Uber has been working on in terms of being a multi-modal platform,” Rzepecki said.

Meanwhile, Uber’s international competitors have made similar moves. India-based ride-hailing startup expanded into bicycles in December. Called Ola Pedal, the service is available on a handful of university campuses in India. Then there’s Southeast Asia’s Grab and China’s Didi, which both launched their own respective bike-share services this year. Both Didi and Grab have also invested directly in bike-sharing startups Ofo and OBike, respectively.

With JUMP under the ownership of Uber, we likely won’t see JUMP partner with any of Uber’s direct competitors, but Rzepecki said other types of partnerships could be interesting.

“I think the idea of us being inside the Lyft app is not necessarily likely but there may be other partnerships that we’re able to do that are less directly competitive,” Rzepecki said.

In January, JUMP closed a $10 million Series A round led by Menlo Ventures with participation from Sinewave Ventures, Esther Dyson and others. JUMP’s January funding brought its total amount raised to $11.1 million. That same month, JUMP became the first stationless bicycle service to receive a permit to launch in San Francisco. Since then, JUMP has launched 250 dockless, pedal-assist bikes on the streets of San Francisco. Currently, people take between six to seven rides per day, with an average trip length of 2.6 miles, Rzepecki said.

“We really know we are serving a commute,” Rzepecki said. “We’re serving the morning and evening commute. I think 22 percent of trips are in the morning and 20 percent in the evening commute. We’ve really been a commuting solution.”

In October, the SFMTA will determine if JUMP can deploy an additional 250 bikes. The SFMTA will make its decision based on an evaluation of the program’s first nine months. That evaluation, the SFMTA told TechCrunch in January, will entail determining where the city should promote stationless bike-share, the impact stationless bike-share has on the public right-of-way, “including maintaining accessible pedestrian paths of travel, as well as the enforcement/maintenance burden on city staff.”

JUMP also operates its e-bike network in Washington D.C., and plans to launch in Sacramento and Providence, Rhode Island later this year. Through its software and hardware offerings, it operates via third-parties, like cities, campuses and corporations, in 40 markets including Portland, New Orleans and Atlanta. JUMP is also interested in deploying its bikes in Europe, where it hopes to be by spring of 2019. JUMP has also applied for a permit to operate in New York, which recently legalized electric, pedal-assist bikes.

E-bikes, of course, are not the only way to get around town these days. This year, we’ve seen a number of startups launch electric scooters. While San Francisco is trying to figure out how to regulate them, people are watching closely to see what comes next.

Khosrowshahi is one of those people. He told me he’s been “staring at some of them quizzically on the streets.”

Scooters are in an “odd spot” due to the lack of regulation, Khosrowshahi said, but Uber will “look at any and all options” that “move in a direction that is city friendly.”

Additional reporting by Katie Roof.